(Kayla Mayer/TommieMedia)

São Paulo or Gotham City? Sunny skies turned dark in the middle of a late-August afternoon, transforming the city into a gloomy skyline worthy of a DC comic.

But São Paulo isn’t afflicted by the likes of the Joker and the Penguin. Day became night as a cold front brought with it the smoke from the widespread wildfires in the Amazon rainforest.

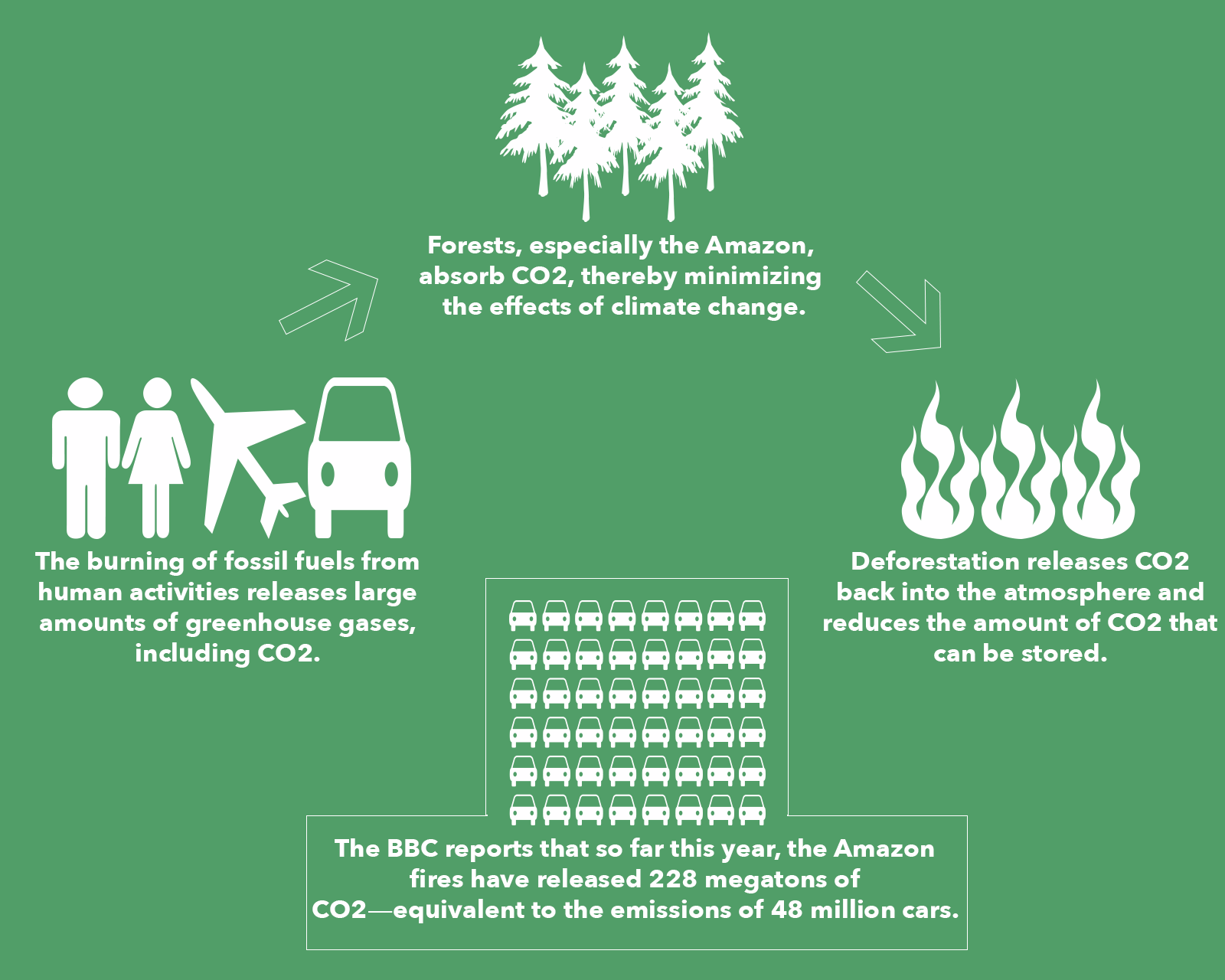

Although fires in the Amazon are common at this time of the year, 2019 has experienced the highest amount of wildfires since 2010, with more than 10,000 square miles of land affected so far. This year has also seen the highest amount of carbon dioxide released since 2010 due to the blazes. The European Union’s earth observation program, Copernicus, says the more carbon dioxide released, the more destruction is occurring.

Why the increase?

Brazil’s economy relies on the rainforest, which contributes $8.2 billion a year. Farmers, loggers and other small groups deliberately set fires because they benefit from clearing areas of the forest for pasture, crops and wood. Since Brazilian authorities haven’t cracked down on the rising deforestation, these small groups know that even if they are caught, they won’t be punished.

Combining this rampant deforestation with the rising global temperature leads to the ideal conditions for fires to spread. Yadvinder Malhi, a professor of ecosystem science at the University of Oxford, told BBC News that the South American climate would suffer the immediate effects of the fires. If large amounts of the rainforest are destroyed, the continent would receive less rainfall, hurting agricultural areas and possibly making others unlivable.

Worldwide impact

However, the wildfires aren’t just a South American issue; they’re a global issue. Scientists say the fires could also make the Paris Agreement’s climate goal harder to achieve. The Amazon stores some of the carbon dioxide produced by humans, and deforestation releases its storage back into the atmosphere.

Climate impact aside, the Amazon also houses rare and diverse plant and animal species, many of which remain unknown. The earth’s largest rainforest and most biodiverse region holds billions of trees, thousands of plant species and millions of animal species. Many of these would be lost if the rainforest collapsed.

What’s been done so far

So far, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has called in the armed forces, sending 43,000 troops to fight the fires, and Chilean President Sebastián Piñera presented a two-step solution in August consisting of a collaboration between Amazonian countries to fight the blazes, to protect the rainforest’s biodiversity and to work on reforestation.

Donations to fund these efforts have poured in, including those from celebrities and other countries. Earth Alliance, a charity co-chaired by Leonardo DiCaprio, pledged $5 million to protect the Amazon. Britain and Canada pledged $12 million and $11 million respectively. The Group of 7―the US, UK, Germany, Canada, Japan, France and Italy―pledged $22 million, a disappointing number coming from the group of countries that represent 40% of the global domestic product.

Bolsonaro’s rebuttal of the G7’s meager donation doesn’t help. He even attacked French President Emmanuel Macron on Twitter, saying, “The French President’s suggestion that Amazonian issues be discussed at the G7 without the participation of the countries of the region evokes a misplaced colonialist mindset in the 21st century.”

If the G7 wants more of a say in what happens to the rainforest, they may want to consider bigger donations in the future.

Looking to the future

Despite what Bolsonaro says, I argue that the issue of protecting the Amazon doesn’t have borders since it affects the global climate and that the key to saving the rainforests lies in the hands of policymakers.

Environmental protection has been weakened since Bolsonaro took office in January 2019. His encouragement of mining and farming in the Amazon empowers workers to participate in the already widespread deforestation. The National Institute of Space Research in Brazil recently released evidence that deforestation spiked in June and July under Bolsonaro’s leadership.

And a decrease in deforestation is not in sight. The Integration of the Regional Infrastructure of South America, a multi-nation plan to create means of transportation in the rainforest, is only accelerating this process with the announcement of plans to build a bridge across the Amazon River and pave a road to Brazil’s northern neighbor, Suriname. Through IIRSA, the countries in the Amazon Basin hope to connect their economies and remote areas.

The Amazon first opened to development in the 1970s, and every year since, fires have been set to clear the way for farming. The repeated barrage of the forest with flames is leading the area down a spiral of drought, fire and tree death.

Scientists are unsure how the destruction of the Amazon rainforest would affect the global climate, but rainfall patterns in North America, Europe and Africa would change at the least.

However, the efforts made to limit climate change by cutting carbon dioxide emissions from transportation and manufacturing would be futile if the carbon dioxide contained in the Amazon’s vegetation were released into the atmosphere.

If deforestation isn’t curbed, the Amazon will reach a point of no return. The issue is a global one, and political leaders need to come together to protect the rainforest. Economic policies to preserve the Amazon and cut down on deforestation need to be enforced, or the destruction will only get worse.

Kayla Mayer can be reached at maye8518@stthomas.edu.