(Maggie Stout/TommieMedia)

The world is in the midst of a humanitarian crisis.

The UN Refugee Agency reports that as of June 2019, there are 25.9 million refugees worldwide.

But this refugee “crisis” implies that the refugees are the issue. In recent years, that mindset has been at play in American media and politics. The topic of debate is what to do with people seeking asylum, rather than what to do about the situation they’re leaving.

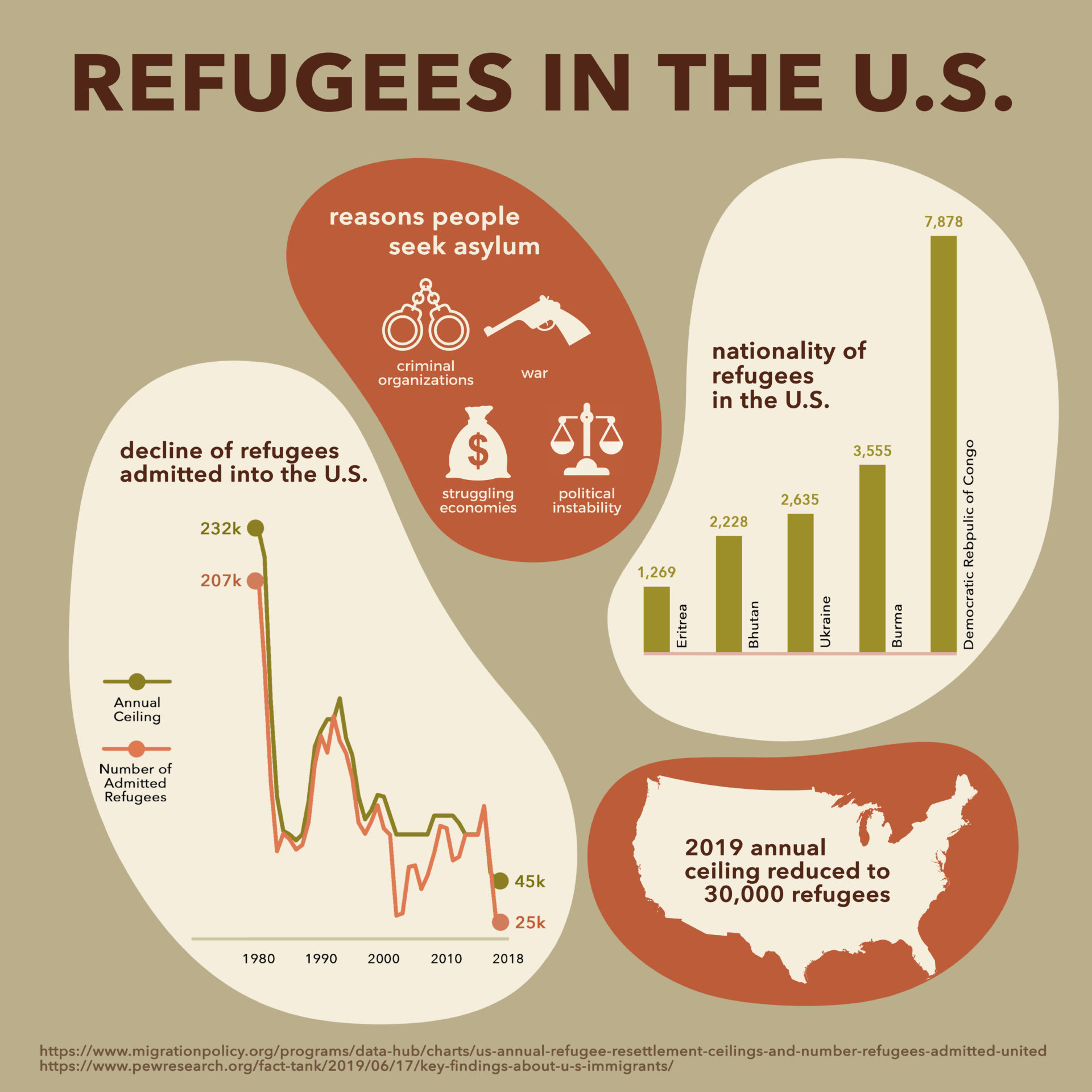

The Trump Administration has limited asylum requests and reduced the maximum number of refugees admitted. Even with the reduction from 54,000 to 45,000 for 2018, the US failed to meet that ceiling and is projected to come up short again on the 30,000 threshold for 2019. If the US did resettle 30,000 refugees that would still be less than 1% of refugees worldwide.

The 45,000 figure was already the lowest refugee admission cap since the adoption of the Refugee Act of 1980. As the number keeps decreasing, we need to re-evaluate whether we’re acting out of our own “protection” or out of prejudice.

If the US hasn’t already broken the 1951 UN Refugee Convention Agreement, then we’re getting close. The agreement grants certain rights to refugees, including the rights to not be expelled and to not be punished for illegal entry.

The separation of children from their parents at the southern border does not look good for a country that has recently withdrawn from the United Nations Human Rights Council. The Human Rights Council promotes global human rights and addresses such violations. While America can still fight for human rights without being on the council, our withdrawal sends a message that we’re not as committed to these issues, and the conditions on the southern border support that.

Refugees do not leave their homes because they want to; they leave because they have to. Lowering the number of refugees admitted, along with making it more difficult to request asylum, comes from a place of ignorance and apathy.

In the words of Viet Thanh Nguyen: “Refugees are unwanted where they come from. They’re unwanted where they go to.” Sadly, the United States’ efforts to limit the amount of refugees admitted only proves the truth of this statement.

While it’s certainly important to develop a better system for helping refugees, the focus of our efforts should be on alleviating the violent and dire situations―such as poverty, drug and human trafficking, political instability and economic collapse―that they’re fleeing.

By understanding the catalysts behind their exodus, we can decrease the number of people who feel they have to leave and take some of the pressure off of our immigration system. The Trump Administration’s “solutions” only swept the issue under the rug; attacking the roots will keep the pile of dirt from getting any larger than it already is.

So what are some of the reasons that people seek asylum? Criminal organizations, war, political instability and struggling economies put people at risk of violence and poverty. Helping establish order and increasing economic development in countries beleaguered by these issues would create a better quality of life for their citizens.

If the US committed $1 billion a year over the next five years to fund small businesses, jobs, education and criminal justice reform in Central America, scholars and law enforcement leaders hold that it would reduce migration. That $5 billion is significantly less than the most recent $18.4 billion sum needed for a border wall.

The topic of refugee resettlement and immigration isn’t a political issue; it’s a humanitarian issue. It’s time to look outside of our own borders and help others make their homes a safe place to live.

Kayla Mayer can be reached at maye8518@stthomas.edu.