The wrong crowd

William Bulger said that it was around this time that Whitey fell in with a crowd involved in bank holdups and in 1956 was convicted of involvement in three bank robberies and sentenced to 20 years. He served part of what turned out to be an 11-year sentence in Alcatraz.

Four years after Whitey’s conviction, William was first elected to the Massachusetts House.

In the years following Whitey’s release, William blamed the media for spreading what he called “lurid allegations” about his brother, speculating that some of the “dark rumors” were nothing more than political attacks on him.

As Whitey’s criminal activities appeared to turn more brutal, William Bulger rose through the Statehouse ranks. In 1970, he won a Senate seat and eight years later was elected Senate president, a position he would hold for a record 17 years.

Even after Whitey fled in 1995 of the eve of his indictment on racketeering charges, William remained loyal, accusing overzealous prosecutors of buying testimony with promises of early release from prison.

“It has been known for many years that a ‘get out of jail’ card has been available to anyone who would give testimony against my brother,” he wrote.

At the same time, William was earning a reputation as a tough-minded leader who rewarded supporters and punished critics.

Warren Tolman, a former Democratic senator who was among those critics, served briefly under him.

Tolman said that although he often found himself at loggerheads with William Bulger, he felt Bulger treated him fairly and could be “a charming guy” when he wanted.

Still, Bulger wasn’t shy about using his political might.

Tolman said after he was able to prevent a transportation funding proposal from passing by a single vote, Bulger, who opposed the measure, used his muscle to flip a vote, forcing the proposal through.

“By and large he got his way whenever he wanted,” Tolman said. “You knew that if you took him on it was going to be an uphill battle.”

Politicians “knew of the legend”

Tolman said he never recalled open discussions about Bulger’s brother even though his Senate colleagues “certainly knew of the legend of Whitey Bulger.”

“I don’t think anyone ever realized the scope of the dastardly deeds he’s accused of,” Tolman said.

Occasionally the lines between politics and the underworld blurred.

In 1994, state Sen. William Keating led a group of like-minded liberal lawmakers in an attempt to oust Bulger as Senate president.

Although the challenge failed, the campaign against Keating was fierce. Keating said his supporters from South Boston told him that Whitey had paid people to travel to Keating’s district to hold signs for his Republican opponent.

Keating said he had his own brief run-in with the reputed mobster, who approached him and lit into him with a barrage of profanity-laced insults for trying to take down his brother.

Keating, who went on to become Norfolk district attorney before being elected to Congress last year, said he’s friends with a family who lost a loved one to Whitey’s violence, according to the indictments against him.

“There’s a tendency to glamorize abuse of power and a tendency to glamorize the gangster life, but as a district attorney, I was there as they were unearthing the bodies of (Whitey Bulger’s) victims,” Keating said. “It’s not funny and it’s not glamorous. It was savage and it was brutal.”

In a written statement following Whitey’s arrest this week, William Bulger said he wished to “express my sympathy to all the families hurt by the calamitous circumstances of this case.”

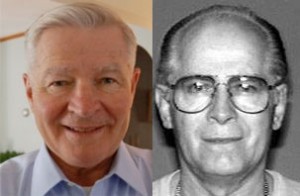

Then, during Whitey’s brief appearance in federal court in Boston on Friday, the aging brothers had a fleeting reunion of sorts. Whitey, now 81, smiled at his younger brother and mouthed the word “hi.” William smiled back.

William, speaking briefly to reporters as he left the courthouse, appeared emotional.

“It’s an unusual experience,” he said.